Problematic History

The grassy lawn has become a staple of the American landscape especially in suburbia. It is a point of pride for some and a chore for others, but regardless, it is something generally seen as commonplace and expected. But in recent years, as overall environmental conscientiousness has increased, a more critical eye has been turned on the familiar structure, and for good reason.

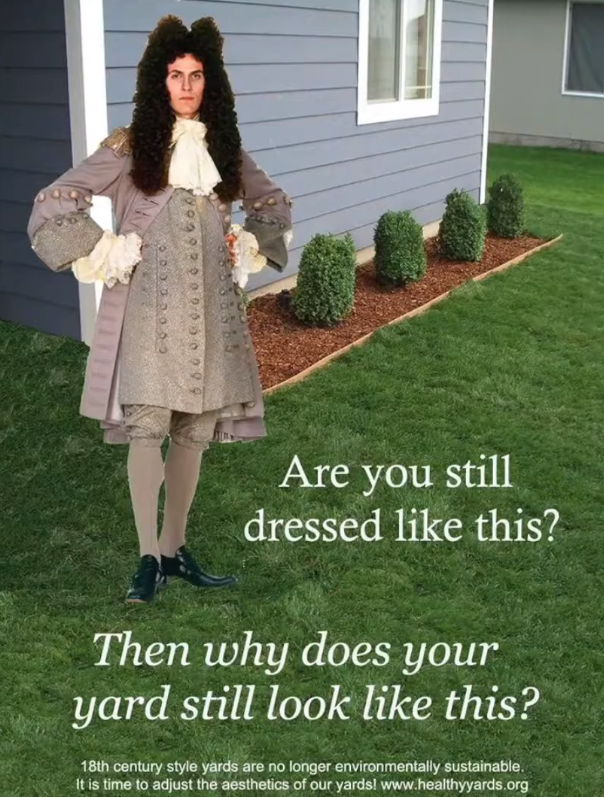

In an abstract sense, the concept of a front lawn and the emphasis on the uniformity of it can be seen as a classist holdover from both wealthy Western European society and early-mid-century industrial America. Wealthy European landowners often displayed their wealth with swaths of heavily curated greenery surrounding the home. As such, many colonists who owned land in North America sought to emulate this1 and gain a sense of home via the replacement of native, tall, annual grass species with European perennial and pasture varieties2. Then, post-1945 its place as an indicator of a secure, responsible, and domestic American citizen2 was further cemented by the idyllic image of the suburban nuclear family3. Through to today, the state of one’s lawn affects social perception of the occupants of its accompanying house, and potentially of the neighborhood surrounding1. One need only look to many modes of traditional horror stories and the idea of “overgrown-ness” and disrepair that categorizes many haunted or evil homes and witch’s lairs. Although, I will relent that such assumptions have eased a bit in more recent years.

On the environmental end, issues with the turf grass lawn are numerous. First, there is a great amount of energy, water, and chemicals put into maintaining lawns. Estimates put the average cost at ~10,000 gallons of water per summer and ~70 million pounds of chemicals per year. Plus, there are other costs like the cost of gas for mowing, yard waste, plastics implemented directly or indirectly to block weeds, etc3. The high maintenance is largely due to the fact that the ideal lawn is a lush green monocultural (single-species) swath, which is by most stretches unnatural, especially for this area. If left to its own devices, an area will grow a mix of plants based on what seeds are around and what plants thrive in a particular climate. Even with competition, it is almost never the case that one seed outcompetes all others.

Beyond this, monoculture can be hazardous to the soil. Each type of plant draws out and replenishes different things from the soil, and as such, if only one thing is grown in an area over and over again and there is no natural replenishment, a severe ecological imbalance can occur and compromise the integrity of the soil &/or otherwise impact the rest of the surrounding ecosystem1. This increases demand for fertilizers and chemical supplements1, as well as the likelihood that the grass will not remain lush and green the way many desire and possibly (be assumed to) require replanting with new seeds or sprouts. Without extrapolating too much, the increased use of fertilizers in both residential and agricultural areas increases nutrient-rich runoff into local waterways which can cause eutrophicationa events, extending damage beyond the immediate system.

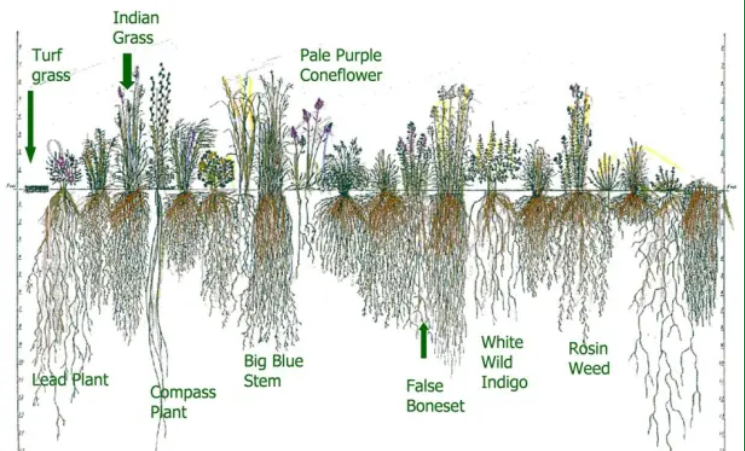

Nutrients are not the only thing that can wash out either. Monoculture can also encourage the proliferation of various plant diseases, funguses, insects, etc. that feed on a particular species1. To combat this and/or to keep the verdant green color desired, many lawn owners spray pesticides and other chemicals that can pose a threat to local pets and wildlife and can also be washed out into waterways. Furthermore, turfgrasses tend to have shallower root systems than other, native North American grasses (see image below). This not only doesn’t hold the soil as well, but also means the roots can’t interact with the water, nutrients, and microbes deeper within the topsoil4. This also contributes to the water-demanding and easily browning nature of many lawns.

Diagram of root systems for various grass species comparing depth of turf grass systems (far left) to various other varieties of native North American grasses and flowering plants4

Diagram of root systems for various grass species comparing depth of turf grass systems (far left) to various other varieties of native North American grasses and flowering plants4

Regardless, for better or worse, lawns and their imported short, turf-style grasses are a near-ubiquitous part of life. And while there is a part of me that wants to advocate for the gradual abolition of lawns altogether (and if you are so inclined I surely wouldn’t stop you), I know for many that is not feasible or desirable. Instead, the subsequent paragraphs will seek to offer some means of improving the ecological health and sustainability of a lawn.

What do I do then?

The first thing to do is to take stock. Look into your lawn habits and try to find areas that may be contributing to the above issues. Consider if all of the things you do are necessary. Some places to start are as follows:

-

Do you know what type/species of grass you have?

-

Is it appropriate for the south jersey zone (6-7) and the amount of sun vs. shade you get?

-

How often do you mow?

-

Are you watering your lawn?

-

Do you fertilize or use pesticides?

-

What methods of weed control do you use?

-

Do you replant every year?

-

What do you do with grass clippings?

Once you have assessed your current practices, look for specific areas and what you can do to improve. There are lots of different ways to approach this topic, but I’ll offer a few below.

The first recommendation I have is the simplest and most cost-effective. And that is to do nothing. Quite literally, allowing “weeds” to mix into your existing grass(es), and not watering, fertilizing, or spraying can make lawn-owning more environmentally friendly. This does assume that the existing turf-grass is properly acclimated to the area and conditions of one’s location (see next paragraph). That aside, this method saves on water, energy, and money. It also provides a more polycultural environment. Additionally, this method can result in some very interesting volunteer plants, including some native and potentially edible varietiesc (i.e. dandelions, purple dead nettles, and blue-violets). Most plants we consider weeds, like the ones mentioned parenthetically, are actually beneficial to the soil and to other creatures like pollinators.

The “do nothing” category also includes mowing less and letting lawn clippings and fallen leaves stay on the lawn. Most turf grasses grow relatively slowly, and frequent mowing actually contributes to the shallowness of the root system by diverting energy into regrowing the blades to a length necessary to keep the grass alive4. As for the lawn clippings and fallen leaves, allowing them to decompose properly and among the grass will allow the soil to reabsorb some of the nutrients stored in those cells.

Secondly, consider changing the type of turf-grass you have to one that won’t require as much maintenance based on where you live.

Grass Type |

Light Requirements |

Drought Tolerance |

Growing Season |

Growth Rate |

Heavy Foot Traffic Tolerance |

Unique Care Requirements |

Tall Fescue* |

sun |

good |

year-round |

fast |

poor |

|

Dwarf Tall Fescue* |

sun |

good |

year-round |

moderate |

poor |

|

Double- dwarf Fescue |

sun; tolerates light shade |

good |

year-round |

slow |

poor |

|

Hybrid Bermuda |

sun |

good |

warm seasond |

fast |

excellent |

not for shaded areas |

St. Augustine |

tolerates shade |

good |

warm season |

moderate |

moderate |

|

Kentucky Bluegrass* |

sun to semi-shade |

poor |

cool seasone |

moderate |

good |

avoid hot, full-sun exposure |

Perennial Ryegrass* |

sun |

|

|

fast |

good |

does not self-repair |

Zoysia Grass |

sun |

good |

warm season |

|

excellent |

|

Seashore Paspalum |

sun |

moderate; salt tolerant |

warm season |

fast |

good |

trails aggressively |

Creeping Red Fescue |

sun to semi-shade |

good |

cool season |

slow |

moderate |

no mowing required |

*Mix with other varieties for improved performance

Attributes and growing conditions for various types of turf grasses to determine what might work best for the reader5

Keep in mind, you can block out different parts of your lawn based on the amount of sun and foot-traffic.

Next, consider planting some native grasses as part of your landscaping. Some quick research will yield a list of grasses that used to be prolific in this area, including switchgrass, indiangrass, little bluestem, big bluestem, and deer tongue10.

Species |

Attributes |

Avg. Root Depth |

Zones |

Requirements |

Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) |

-dense clumps of tall grass

|

Several feet |

3-9 |

-full sun to partial shade

|

Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans) |

-bunchgrass

|

Several feet |

2-9 |

-full sun

|

Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) |

-clumps with equal spread (like koosh balls)

|

5ft |

4-10 |

-full sun

|

Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) |

-clumping grass

|

5-8ft |

3-8 |

-full sun to light shade

|

Deer Tongue (Dichanthelium clandestinum) |

-stems with short branches (2.5”-6”) and large leaves

|

?? |

?? |

-partial sun

|

Table showing the different attributes and requirements of various native NJ grasses to determine if any might work for the reader6,7,8,9

All of these varieties can have additional benefits to you and other parts of the ecosystem, including serving as weather or other plant buffers, screening, and nesting sites for birds and small mammals.

Andropogon gerardii [Big Bluestem] Big Bluestem is tall, attractive, drought-tolerant native grass with colorful foliage and enormous benefits for wildlife. © https://www.jerseyyards.org/

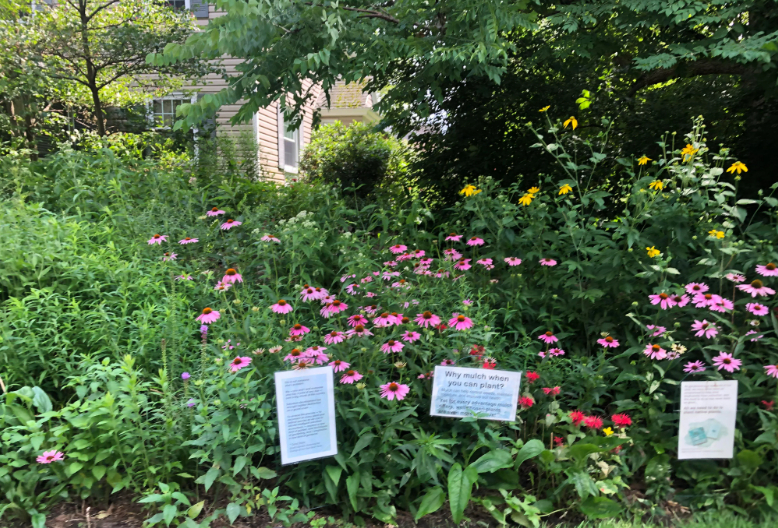

Finally, consider turning parts of your lawn into a garden. This can be sectioned or not, and can consist of flowers, fruits, vegetables, herbs, or any combination thereof. If taking this approach be sure to do research into what kinds of spacing, light, water, and nutrients each plant would require. If you plant things that draw different things out of the soil, you can rotate them seasonally to replenish what was taken each season. Additionally, it would be wise to look into what plants are native to your area as well as any that could pose problems for local plants and animals.

Conclusion

I hope this article provided you with some insight into the phenomenon of the turf lawn and ways that we can make it better for both ourselves and the environment. Happy gardening, or not gardening!

If you would like more info about developing a more sustainable yard please watch this video series by Ed Cohen on how to modernize your yard. Sustainable South Jersey also has educational talks on various topics including creating native habitats and rain gardens. Sign up for our newsletter here to stay informed of our upcoming Meetups and visit our Education section for interesting articles.

Resources:

Notes:

aEutrophication: literally nutrient-plentiful, a process in which an excess of nutrients in water systems creates a chain reaction of negative effects for that ecosystems, usually beginning with massive algal blooms

bVolunteer Plants: individuals of non-cultivated plant species that grow in an area

cPlease note that I don’t actually advise eating plants from your lawn unless you don’t or have not sprayed for at least a year and are absolutely sure what it is

dWarm Season Grass: grows in late spring through the summer

eCool Season Grass: grows most actively in spring and fall

References:

1Loewus-Deitch, Daniel. “Why You Would be Wise to Trade in Your Lawn for an Urban Garden.” (2011).

2Robbins, Paul. Lawn people: How grasses, weeds, and chemicals make us who we are. Temple University Press, 2012.

3Groth, Paul. “The Lawn: A History of an American Obsession.” (1994): 296-299.

4https://blog.petersoncompanies.net/why-your-lawn-has-an-unquenchable-thirst-for-water

5Scott Cohen | Updated November 4, 2021. “Best Types of Grass for Your Lawn.” Landscaping Ideas, 26 Jan. 2022, www.landscapingnetwork.com/lawns/types.html#:~:text=The%20%22toughest%22%20grasses%20(considering,Bermuda%2C%20hybrid%20Bermuda%20or%20zoysia.

6“Find a Plant: North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox.” Find a Plant | North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants. Accessed 30 June 2023.

7susan.mahr, Written by. “Switch Grass, <em>panicum Virgatum</Em>.” Wisconsin Horticulture, hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/switch-grass-panicum-virgatum/#:~:text=It%20is%20hardy%20in%20zones,short%20rhizomes%20in%20all%20directions. Accessed 30 June 2023.

8(http://www.clarity-connect.com), Clarity Connect. “New Moon Nurseries.” Sorghastrum Nutans Indian Grass from New Moon Nurseries, www.newmoonnursery.com/plant/Sorghastrum-nutans. Accessed 30 June 2023. *(replace species name with others for other native grasses)

9Plant Fact Sheet – USDA, plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/factsheet/pdf/fs_dicl.pdf. Accessed 30 June 2023.